Mount Hood seemed to celebrate statehood with fireworks

Northwest Oregon's mountain playground hasn't always been such a benign place; when the members of the Mazama Club held their meetings on top of Mount Hood, they were picnicking on an active volcano.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2017 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

This postcard image, with correspondence on it

dated 1916, shows the

mountain with some

fancifully colorized roadside shrubbery and an

early-1910s runabout. For a larger image, click

here.

By Finn J.D. John — September 6, 2009

Most Oregonians know the state was founded on Valentine’s Day, a little over 150 years ago. And there may have been some fireworks set off to commemorate the occasion.

But the biggest fireworks display set off on the year of Oregon’s statehood had nothing to do with the politics of what was then the newest state in the union.

In September of 1859, seven months after the state was founded, Mount Hood erupted.

It’s odd to think about Mount Hood as an active volcano today. The mountain has sat there, majestically resting, ever since anyone alive today can remember — although it did do a bit of steamy grumbling in 1907.

Every winter thousands of happy Oregonians slide down its sides on skis and inner tubes, and hundreds more clamber all the way to the top. Mount Hood is the second most climbed mountain in the world, after Japan’s Mount Fuji. (New Hampshire’s Mount Monadnock gets more climbers, but is only 3,165 feet high. That's just 700 feet higher than Mount Constitution on Washington’s Orcas Island, which gets many times more climbers than both Hood and Monadnock combined, many of whom pedal all the way to the top on bicycles. It all depends on one’s definition of “mountain.”)

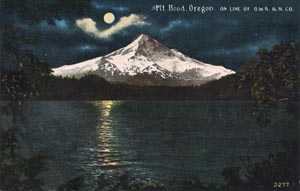

This picture postcard, dating from circa 1930,

shows a nighttime view of Mount Hood as seen

across Lost Lake. For a larger image, click here.

On Mount Hood, climbers today worry a lot more about the unpredictible weather than volcanic eruptions. But this wasn’t always so.

In fact, just before Lewis and Clark made their expedition to Oregon in the first decade of the 1800s, Mount Hood erupted spectacularly. In a “prequel” to the Mount St. Helens eruption that would come 180 years later, the mountain belched out a massive cloud that deposited a layer of ash for miles around – six inches thick on the mountain’s flanks.

This episode kicked off a spate of fiery activity on top of Oregon’s tallest mountain that lasted 50 or 60 years. Oregon newspapers reported excitement on the mountain in 1853, 1854, 1859 and 1865.

The 1859 eruption is particularly interesting because, of course, that’s the year Oregon became a state. According to a pioneer named W.F. Courtney, quoted by author Bill Gulick, “It was about 1:30 in the morning when suddenly the heavens lit up and from the dark there shot up a column of fire. … For two hours as we watched the mountain continued to blaze at irregular intervals. …”

It was almost as if God himself had decided to set off fireworks to celebrate statehood, although such an idea is preposterously presumptuous and — depending on your religious feelings — quite possibly blasphemous.

Still, it’s interesting to think, during a stay at Timberline Lodge or a day trip to Mount Hood Meadows, that one is playing on an active volcano that, actually, could burst into fiery activity at any time.

And it’s also interesting to reflect that when former Albany newspaperman William Gladstone Steel founded the Mazama Club in 1894, the act of climbing that mountain — a prerequisite for membership — wasn’t just a technical challenge. It was a risk as well. Members could say they had climbed the state’s most active and dangerous volcano and lived to tell about it.

(Sources: Gulick, Bill. Roadside History of Oregon. Missoula: Mountain Press, 1991; www.portlandhikersfieldguide.com)

Note: More images of Mount Hood are with the story on Timberline Lodge (click here).

-30-