Lumberjacks' Saturday Night

A night of hell-roaring by a logging camp crew was a far different thing in the mid-1940s than it had been just a dozen years before.

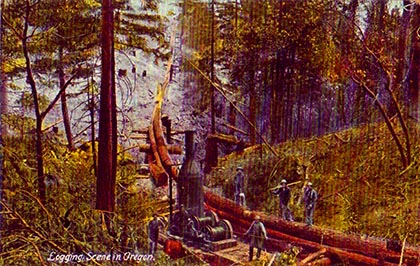

A postcard image from the first decade or two of the 20th Century,

showing a logging crew with their engine.

By Stewart Holbrook — March 1943

A wan December sun struggled briefly against the heavy clouds, then gave up, and the winter gloom of the Pacific Northwest settled down to bring night at four o’clock. All along the single street, the pavement began to gleam in the rain as one by one the neon signs came on in the score of false-front hotels, restaurants, stores and beer joints. Sifting through the leaky sides of the joints came the music of juke boxes, played by slugs furnished by the proprietors themselves, for Saturday night was coming to Chokertown and it has long been an axiom here that the joint with the most light and the most noise gets the business.

“Business” in Chokertown means loggers, lumberjacks. Less than half a mile from the High-Lead Hotel, in the center of town, begins the vast forest that runs almost uninterrupted for a hundred miles west to the Pacific shore and fifty miles east to the top of the high Cascade range. It is a tremendous forest and here in the rain belt it is growing fast enough, so many foresters say, to keep Chokertown’s loggers busy until the Round River freezes solid and alcohol and snuff drip copiously out of hemlock bark.

There, in an opening of this forest, stands Chokertown, already fifty years a lumber town but now getting a new lease on life as a place of entertainment also, a blow-in town, a whoopee place for lumberjacks.

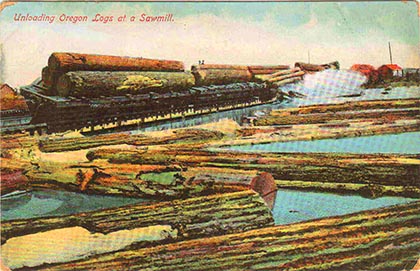

This early postcard image, probably from the late 1890s or possibly the

early 1901s, shows a logging crew working with a steam donkey engine.

Tire and gas rationing first brought Chokertown its new night life. It was really a revival, for, a quarter of a century ago, Chokertown made lumber and also served as a place for loggers to blow her in. Then came the automobile and the good roads. Roads led right up to camp doors in the tall timber. No longer had a lumberjack to toil for six months without going to town to “get his teeth fixed” — as it is euphemistically termed. He could go to town every night in the week, if he wanted to. And he did. He spent a little but not much money, and returned to camp the same night. But this new-style lumberjack seldom went to Chokertown at all; he lit out for Seattle, for Aberdeen, for Bellingham — the big towns. So, small Chokertown kept on sawing the logs into lumber and lived a rather staid life. The great whoopee days had gone, never to return — or so most people thought — even though Chokertown’s mills produced millions of feet of lumber every year.

Then, in 1940, began a demand for lumber the like of which had never been seen — lumber for cantonments, for hangars, for ships, lumber without end. Pearl Harbor set loose a new and greater demand which continued unabated through the war years and after. Prices hit the ceiling and so, finally, did wages in the woods.

An early 1900s hand-tinted postcard showing a load of logs being dumped

into a mill pond for processing. Whoever tinted this postcard either had

never seen a log pond, or didn't care; the water in those ponds is black, like

strong tea, not blue.

Along came the tire menace. At first the loggers, like other folks, gave it little thought: but as old tires gave out, the logger found he would have to stay in camp nights, or walk — usually a matter of from 20 to 40 miles. So the jacks stayed in camp, listening fitfully to the radio, or boredly to old-timers who liked to do some stove-logging. The younger jacks soon tired of such doings, for they were not accustomed to six months solid of camp life, or even six weeks of camp life, without a break. They pooled the surviving travel equipment — a couple of tires here, a couple more there, and a car — and ganged up for a trip to town on Saturday night. In many cases, it was not too difficult to persuade the bull of the woods, the logging boss, to run a train to town right after Saturday’s whistle. It became a habit.

"Look out, Chokertown, here we come!"

So, last Saturday night, just as it has done on many Saturdays recently, the Two-Spot coupled up a mulligan car and a caboose at Camp Six of the Dosewallops Logging Company. The lokey’s whistle let go a blast, and inside of two minutes, one hundred and forty loggers piled aboard. The Two-Spot’s bell rang and she started with the train for Chokertown, twenty miles away.

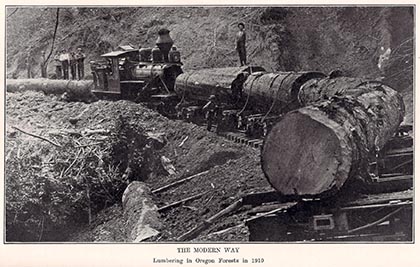

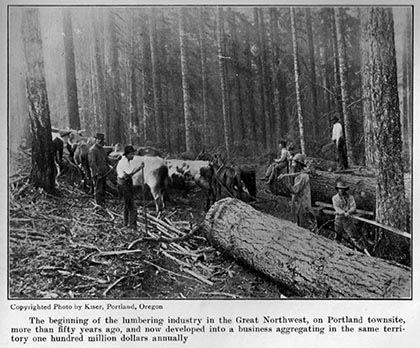

A picture from "History of Oregon" by Joseph Gaston, showing the

"modern way" of logging; the book was published in 1911.

“We’re the blue-eyed, bandy-legged, hump-backed old mackinaw hodags from Dosewallops!”

Down, down the mountain, across high trestles, over dizzy canyons rolled the two carloads of lumberjacks, while the Two-Spot moaned and chugged, letting go a blast on the curves. Inside the swaying, bounding cars, young loggers shouted pleasant obscenities to each other. The lokey rattled on.

“Look out, Chokertown, here we come! Eighty feet to the nearest limb and six foot through at the butt!”

The Two-Spot’s bell began to ring. The whistle sounded. The train crossed a switch with a clatter and ground to a stop at the log dump beside the river and less than 20 yards from the main street. Under blinking lights, the boys from the woods could see some of their handiwork — the log pond of the big sawmill filled with sticks, big ones, the stuff they had felled and bucked and sent to the saws. Under the lights, the pond men were still working, feeding the huge logs to the bullchain that took them up the curved slip and on to the whining bandsaws. Mills can work all night. Loggers can’t.

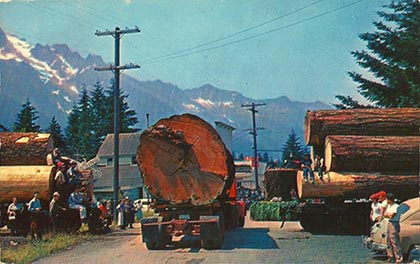

The late 1940s were an exciting time to be involved in the logging business

in Oregon; one-log loads like this one were common. This postcard claims

to show a town in Oregon, although it doesn't say which one.

II

In half an hour, Chokertown was alive. I went to the High-Lead first and found the bar lined two deep, all drinking beer, the only drink served. The overflow stamped into Joe’s Tavern and the Logger’s Rest, two other beer places. A few of the more serious drinkers did not stop at all until they got to the State Liquor Store, where the State of Washington purveys hard stuff at rather high prices.

“NO LIQUOR TO BE CONSUMED ON THE PREMISES,” says a sign.

“Who the hell wants to?” It was Dan Peters, a tall and rugged hooktender from Dosewallops. With two pints of rye in his tin coat and two chokerman pals similarly rigged, the three headed direct for the Stockholm.

The Stockholm is not the fanciest place in town, but it has that something about it which attracts young and older loggers who take their fun as seriously as their work. Its modest neon sign, looking so modern and new against the false front of weatherbeaten boards, says simply that this is “The Stockholm, Good Food, Beer, Rooms.” Inside, too, the Stockholm is a mixture of periods. It is one great room with a bar down one side, booths on another, food counter at the rear. In the exact center is a gigantic barrel stove, its pipe running nearly 10 feet to the high ceiling, then ranging 30 feet through haywire loops to the rear wall. The floor between stove and lunch counter is broken only by one of the biggest and gaudiest juke boxes to ever come out of Chicago. It is lighted like Borealis and it fairly gleams and leers.

Above the bar, and hiking back to five-cent-beer days, is the conventional moth-eaten deer’s head. Back of the bar stands Gus himself, the only bartender left in Chokertown with an indubitable walrus mustache. The bar gleams from polish. The glasses are piled in intricate patterns. A small framed sign contains a one-dollar bill and a historic notation: “First Dollar Taken Over This Bar, August 22, 1899.”

“Hallo, falers,” Gus greeted the arrivals. The booths already were filled with loggers, loggers and girls, guzzling beer or beer spiked with rye. The juke was hitting “Somebody Else is Taking My Place,” loud enough to be heard above the alcoholic laughter. Half a dozen couples were on the floor. Not a mackinaw on the men, but all in conventional city clothes. Dan the hooktender and his pals sit down in a booth where four half-consumed glasses of beer still sat on the table. Just then, the juke ceased for a moment and two couples came to the booth. And right here marked, better than anything else could, the change that has come over lumberjacks. The two couples were strangers to Dan and his pals. They had obviously been occupying the booth. But no roughhouse ensued.

“Guess we took your booth,” Dan said, starting to rise. “Sorry.”

“That’s all right,” one of the strangers spoke up. “We can all squeeze in.” They did, too. The boys from Camp Six spiked everybody’s beer. Turned out the other two lads were gyppo spruce loggers from the opposite side of the river. In a little while everything was rosy. Dan danced with one of the girls, and later took her upstairs to look at the stars. One of the gyppo loggers passed out and slid under the table, very quietly. Booze and bawds, maybe, but not battle. The lumberjacks’ trinity had lost its third angle.

Over at the High-Lead, loggers still lined the bar and filled the booths, they and their girls. The juke box blared endlessly. I watched while men slid under tables, girls screamed beery laughter or wept into their glasses; and one old battle-ax with a deep bourbon contralto stood up by the juke and sang “Good-bye, Little Darlin’” in a true and musical if husky voice, while a rigging slinger from Hamma Hamma, way to hell and gone over the other side of the hump, wept great tears and told me his girl didn’t love him any more.

Logging Paul Bunyan-style, with a team of bulls dragging logs along a

skid road. Image was published in Gaston's book, in 1911.

The odd thing is that nobody hit anybody. Nobody threw a beer bottle. And those who might have looked closely at the husky contralto’s hands would have seen calluses on them. For eight hours that day she had been “pulling green chain; that is, pulling lumber — boards to you — off the chain in the mill across the river. She was but one of the hundreds of women who were still working in a mill. And now a likely-looking lad rushed over to the big contralto and filled her glass with whisky. She broke into her own song without benefit of the juke music:

“I’m a tearing old stiff full of slivers of sitka/ And I’m packing the wallop that went to beat Hitla.”

“Amen, sister.”

“Hold her, cutie, and watch that rigging.”

The juke blared again and the dancers cavorted. The High-Lead was shaking and shivering in every one of its old boards and timbers. The proprietor told me it was going to be a one-thousand-dollar evening, with no breakage except for possibly a few beer glasses.

“No sir,” he told me, “loggers don’t live in trees any more and they won’t necessarily eat hay if you sprinkle whisky on it.”

In the Red Front Department Store across the street, a young rigging man from Camp Six was ordering a copy of “Trees and Forests of the Western United States,” by Hanzlik, a standard work on forests. In another section of the same store (“We Sell Everything”) a high-climber from Hemlock Bay was buying a whole list of stuff — for his wife back in camp; threads and didies and a cord for the electric flatiron and such domestic things.

Mac’s Barber Shop (four chairs) had a waitiung line and many of the boys were getting the works — shampoo and all — while a Filipino lad shined their shoes, just as though they were city slickers. The talk in the shop, I noted, was not about women and automobiles, but about log production.

Across from the barber shop I could see the windows and sign of Painless Prentice, the chain dentists. Four patients were in the chairs. This was the ultimate, the incredible — loggers coming to town to “get their teeth fixed” and actually going to a dentist! It almost passed belief.

One block away, down on the river bank, a row of three shacks represented all that was left of Chokertown’s onetine full two blocks of cribs. In 1920, the cribs here numbered at least a score and they housed, so old-timers say, sixty women. Tonight, half a dozen women would entertain perhaps as many as twenty loggers, possibly thirty. This doesn’t mean that morals have changed; they never change. It means that many of today’s loggers have wives, either in camp or in town.

I went back to my room at the High-Lead and there, over a few drinks, talked with a forester who had once been a lumberjack. Now he had charge of a forty-acre tree nursery owned and operated by a group of logging concerns.

“So loggers themselves are planting trees in these incredible times?” I asked.

“We’ll plant about eight million this winter,” he said matter-of-factly. “Beginning next season, about ten million a year. We raise them from seed at the Nisqually nursery.”

“Did I understand correctly?” I asked. “Did you say that this nursery is owned and run by the logging operators themselves, the lumbermen?”

“That’s right. And we can raise enough trees at Nisqually to plant every burned-over acre in Oregon and Washington. What is more, we ARE planting them.”

I reflected on the late and terrific Jigger Jones, the old woods boss who swore he wouldn’t leave a tree standing between Bangor and Seattle, nor a virgin anywhere. The times were changing even more than I had thought.

At five minutes to midnight, the Two-Spot blew a blast and I went over to the siding to see how the boys had been making out. Perhaps a score of them showed signs of alcohol — in mild doses. Two were indisputably drunk, but moving under their own power. One was drunk AND had a black eye. Only eight were missing and five of these were married men with wives in town …. In my days in the woods, I recalled, the only ones who would have been ready to return to camp at midnight would have been those who were carried. I watched the boys climb aboard. The bell rang and away went the hell-roarers of Camp Six, back to the timber.

One by one, the lights went out along Chokertown’s main drag until only the High-Lead showed in the dark. I went in and talked with old Bill, the night clerk and chef, about lumberjacks old and new.

“No,” he said, “they don’t kick out windows any more. But one’ll kick hell out of more timber than two of his grandpappies could. They’re highball these days. Don’t spend so much money in town. Nowhere near. Never throw money away, like it used to be. These boys going to get their money’s worth. Hardly ever get to fighting. Jes’ like to drink some beer, to dance them jitter things, play pinball machines.”

I asked Bill if the young loggers were different in any other ways from the old-timers. He eyed me a moment, then spoke slowly and, I thought, sadly. “Well,” he said, “they wear rayon underwear.”

“That’s all?”

Bill turned his bloodhound’s sad eyes on me. “No,” he said, then lowered his voice as one does in speaking of some terrible infirmity. “They smoke cigarettes and use talcum powder after they shave.”

I went to bed. Chokertown had gone to bed, too; that is, all except for the sawmill. I could hear the faint whine of its saws all through the rainy night, and down on the pond I could see men poling logs to the ever-hungry slip. Four miles up the mountain, the Two-Spot sounded a last moan on her whistle as she headed up a ravine, carrying the boys who are better loggers and far shrewder playboys than their fathers were.

— Reprinted from H.L. Mencken's The American Mercury, March 1943