Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

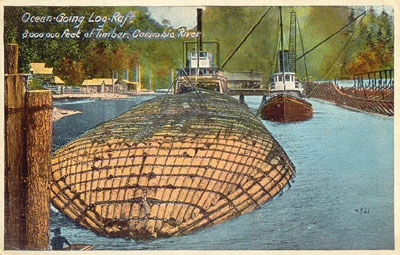

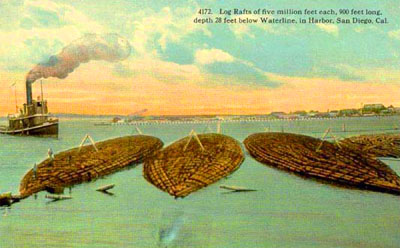

CLATSKANIE, COLUMBIA COUNTY; 1890s:

First seaworthy log raft helped build San Diego

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

Secondly, raw logs were dangerous on a ship at sea. As a load, they shifted easily and developed tremendous momentum when they did. Sure, they’d be chained down, but in rough enough weather chains could break. And finally, some of the logs Benson was getting out of the woods at this time were just too big to fit efficiently in the space available on a lumber schooner. No, another solution was needed. Benson thought he had one: An oceangoing log raft. Nearly everyone thought this was lunacy, and dangerous to boot. But Benson, with his natural engineer’s approach, came up with a system that he knew would work. How they built themIn the quiet waters of Wallace Slough, on the Columbia, Benson’s team built a mammoth cradle, which looked a little like the ribs of a ship. The cradle was filled halfway with logs of various lengths before the chains started getting put on: one mammoth chain down the middle of the raft from one end to the other, with chains radiating out from it to the outside of the raft, where they were linked to a series of external chains that circled the cigar-shaped mass of logs. The finished product contained up to 6 million board feet of lumber, held together by 175 tons of chains. Putting the raft together took weeks; a crane operator had to carefully place each log so that there would be plenty of overlap, to prevent the raft from breaking in two. When the cradle was full of logs, the outside circle chains would be dogged down as tight as they could go and the finished raft would be released into the river. When released from the cradle, the load would spread out a bit, leaving the top flat enough to stack cargo on it, so many Benson rafts made the journey with deck loads lashed on board. The finished product was 835 feet long and about 55 feet wide — just over an acre, being pulled slowly down the coast toward Southern California. Oregon builds San DiegoIt was a great success. Simon Benson got to build San Diego. He settled into a rhythm: During the winter, while the storms raged on the ocean, his crew worked in the quiet waters of the slough, building the summer’s fleet. When the weather calmed down, the cigar-shaped behemoths would start heading out to sea. Out of 120 rafts built, only two were lost to heavy weather. “If we struck rough weather … the steamer cast loose [and] let the raft wallow in the trough of the sea till the storm blew itself out,” Benson later recalled, according to an article in the San Diego Union-Tribune. “Then we reattached the cable to the raft and went on.” Benson’s mammoth log islands were a familiar sight on the West Coast from 1906 until 1941. In that year, the 120th raft actually caught fire. After that, citing insurance issues, the owner — not Benson, who had sold his San Diego operations in 1911 — ended the era of Benson rafts.

|

©2008-2023 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.